Various controversial rituals and customs having their roots in the medieval times are used to defame Sanatan Dharma even today. Despite these practices being defunct for a long time now, they are used to vilify us and are used even today to prove us backward and inhuman. One of these practices is the custom of Jauhar. It is not clear when this practice stopped or rather became unnecessary, but it can be safely said that no one has committed Jauhar in the last many decades at least, probably more but there is no way to be very sure.

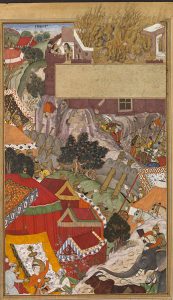

The Burning of the Rajput women during the siege of Chitor

So, what is Jauhar?

Jauhar is mostly a North Indian practice, followed especially in the state of Rajasthan (although there are records of Jauhar being committed in the Malwa region) where women built a huge furnace and stepped into it after which the men went out to fight a battle. It was a form of mass suicide by the women which was followed by all the men going on a suicide mission to fight the enemy.

This practice was by no means a norm. This practice was used as a last resort when defeat seemed inevitable. Also, women committed Jauhar only when the invading army belonged to the Islamic rulers. The same was not the case when the invading King was a Hindu.

Jauhar is invariably accompanied by Saka wherein the men donned saffron robes and went out to battle the enemies. As mentioned earlier, it was a suicide mission. No one survived as far as possible. The sole purpose of this was to inflict as much damage on the enemy as possible before perishing. One has to remember that both Jauhar and Saka are essentially wartime practices. It was not a suicide and was certainly not an act of cowardice. The men fought till their last breath, taking with them as many as they could. An example of their bravery and the carnage that was Saka will be narrated sometime later in this article.

Trying to understand their sentiments through a modern lens is foolishness. The practice looks cruel to a modern intellectual. The women burnt and the men were slain. The number of lives lost would always be humungous. When we look at it now, it all seems unnecessary.

A few years ago Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s movie Padmavat released amidst many controversies. Although historically inaccurate, this movie brought to the fore the practice of Jahur that was otherwise as good as forgotten in the annals of history. With the kind of controversies it raked up, the movie was the talk of the town long before even its teaser came out. Be as it may, Padmavat told every citizen of this country that there existed a practice that was as tragic as it was brave.

Ruins at Chittor

But Padmavat made many intellectuals extremely uncomfortable. Many called this practice a shameful imposition of patriarchy wherein a woman’s honor is invariably linked to her purity while many others raised doubts on the historicity of the events shown in the film. They doubted if Queen Padmini had ever existed. Some of my secular, liberal, feminists went as far as calling Rajput women as cowards for choosing death over life.

These people are not to be blamed. When we look at this in the current context, it seems unfathomable why these women would choose such a painful death over a chance to live? Many articles were written by leading publications on how this movie and this practice was glorifying something that we should be ashamed of.

Rajput honor is the stuff from legends. History remembers the Rajputs as brave, sometimes even recklessly so. Calling them cowards without first understanding what prompted these women to embrace such a terrible death is unfair.

The following an excerpt from Mntakhab ut-Tawarikh by Abd al-Qadir Badayuni. He describes the siege of Chittor and its subsequent conquest in the following words.

“… The Emperor ordered Sabats and trenches to be constructed and gradually brought close to the walls of the fortress. The width of the Sabat was such that ten horsemen could easily ride abreast in it, and it’s height was go great that a man on an elephant with a spear in hand could pass under it. Many of the men of our army were killed by musket and cannonballs, and the bodies of the dead were made use of instead of bricks and stones. After a length of time, the Sabat and trenches were brought up to the foot of the fortress, and they undermined two towers that were close together and filled the mines with gunpowder. A party of men of well-known bravery fully armed and accoutred approached the towers and waited till the towers should fall, and they would enter the fortress. By accident, thought the two mines were fired at one and the same moment, the fuse of one, which was shorter than the other took effect soonest, and the fuse of the later, which was longer, hung fire, so that on of the two towers was blown up from its foundations and heaved into the air, and a great breach was made in the castle. Then the forlorn hope in their impetuosity forgetting the second mine stormed the breach at once and soon effected a lodging. While the hand to hand struggle was going on suddenly the second fuse went off and blew the other tower, which was full both of friends and foes, from its place and lifted it into the air. The soldiers of Islam were buried under stones, some of hundred and some of two hundred man in weight, and the stony-hearted infidels in like manner flew about like moths in that flood of fire. Those stones were blown as far as three or four cosses and the cry of horror arose from the people of Islam and from the infidels.

Nearly five hundred warriors, most of them personally known to the Emperor, were slain and drank the drought of martyrdom: and of the Hindus who can say how many! Night by night the infidels mustering in force kept building up the wall of the fortress from the ruins of these towers.

After waiting a considerable time, six months more or less, at last on the night of Tuesday, 25th of Shaban in the aforesaid year (1567) Imperial troops advancing from all sides, made and breach in the wall of the fortress, and stormed it. The fierce face of Jaimal became visible through the flashing of the fire of the cannon and guns, which was directed against the soldiers of Islam. At this juncture, a bullet struck the forehead of Jaimal who was distinctly recognizable, and he fell dead. It was as though a stone has fallen among the flock of sparrows, for, when the garrison of the fortress saw that their leader was dead, they fled every one of their own houses. Then they collected their families and good together and burnt them which is called in the language of Hind Jauhar. Most of those that remained became food for the crocodile of the blood-drinking sword, and a few of those who remained, who escaped the sword and the fire, were caught in the noose of tribulation. The whole night long the swords of the combatants desisted not from the slaughter of the base, and returned not to the scabbard, till the time for the afternoon siesta arrived. Eight thousand valorous Rajputs were slain.

After midday, the Emperor ordered the sacking to cease, and returned to the camp…

An important point to be noted in this description is that despite the disaster with those exploding mines, the Rajputs didn’t give up. They were still fighting when a lucky shot (as per Abul Fazal the writer of Akbarnama) by Akbar changed things. The siege dragged on for six long months. In the final battle, around eight thousand men (warriors, not peasants. The number of peasants slain is not included in this number) were slain. This was after resisting the siege for six months. The numbers were never well-matched. The Rajputs were far less in number than the Mughal army.

An important point to be noted in this description is that despite the disaster with those exploding mines, which resulted in the death of around five hundred Mughal soldiers and an unknown number of Rajput soldiers, the Rajputs didn’t give up. They were still fighting when a lucky shot by Akbar changed things. The siege dragged on for six long months. In the final battle, around eight thousand men (warriors) were slain. This was after resisting the siege for six months. The numbers were never well-matched. The Rajputs were far less in number than the Mughal army.

Another Mughal historian Mulla Ahmad mentions that “Although the Sabats had thick roofs of cow and buffalo hides to protect the workmen, no day passed without a hundred men more or less being killed…”

Although the Mughals had superior numbers, the Rajputs fought on bravely. This proves that the decision of Jauhar and Saka was not taken lightly. It was taken only in extreme conditions when there was no way out.

One of the very few surviving monuments at Chittorgarh

Abul Fazal in Akbarnama gives a much more detailed and cold-blooded version of the events that happened after Jaimal was wounded/died after Akbar took a lucky shot at him. It is debatable whether Jaimal died from the gunshot or if he died fighting in the Saka that followed. While Mughal sources insist that he was fatally wounded/died from the shot, some Rajput sources claim that he died fighting in the Saka. But one is very sure, after that one lucky shot by Akbar, the tides of the battle turned in favor of the Mughals and the Rajput warriors prepared for the ultimate suicide mission, Saka.

…At this time His Majesty perceived that a person clothed in a cuirass known as the hazar mikhi (thousand nails) which is a mark of chieftainship among them, came to the breach and superintended the proceedings. It was not known who he was. His Majesty took his gun Sangram, which is one of the special guns and aimed it at him…

… An hour had not passed when Jabbar Quli Diwana reported that the enemy had all disappeared within that space of time. Just at the same time fire broke out at several places in the fort. The courtier had various ideas about this, Rajah Bhagwant Das represented that the fire was the Jauhar. For it is an Indian custom that when such a calamity has occurred, and a pile is made of sandalwood, aloes, etc, as large as possible, and to add to this dry firewood and oil. Then they leave hardhearted confidants in charge of their women. As soon as it is certain that there has been a defeat and that the men have been killed, these stubborn ones reduce the innocent women to ashes…

… As many as three women were burnt in the destructive fire of those refractory men…

… When the morning breeze of dominion arose, the active young men and the bold warriors came from batteries and entered the fort, and engaged in killing binding. The Rajput gave up the thread of deliberation and fought and were killed. An order was issued that the active and experienced elephants should be brought in from the front of the Sabat…

… A wonderful thing was that Aissar Das Cohan, who was one of the brave men of the fort, saw the elephant Madhukar and asked its name. When they told him, he, in a moment, with daring rashness, seized his tusk with one hand, and struck with his dagger with the other and said, “Be good enough to convey my respects to the world – adorning appreciator of merit.”

… The elephant Sabdiliya came inside the fort and was engaged in casting down and killing the Rajputs. A Rajput ran at him and struck him with his sword inflicting a slight wound. The elephant, however, did not regard it and seized him with his trunk. Just then another Rajput came in front of him and Sabdiliya turned to him while the first man escaped from his grasp and again daringly attacked him from behind, but Sabdiliya behaved magnificently.

His Majesty also said that in the very heat of the conflict, a hero, whom he did not recognize came under his observation. A Rajput who was separated from him by a low wall challenged him to combat and he joyfully went towards him. One of the imperial soldiers, who also His Majesty did not recognize ran to the assistance of the other hero (Akbar) but the later forbade him saying that it was contrary to the rules of chivalry and courage that he should come to his aid when his opponent had challenged him. He did everything to prevent him from helping him and engaging personally with his opponent he disposed of him. His Majesty used to say that, though endeavoured to find out this brave and chivalrous man, he did succeed.

Abul Fazal has conveniently shifted the blame on the Rajput for killing the women-folk by calling them hardhearted. Mulla Ahmed contradicts him. While Abul Fazal uses an extremely dismissive tone while talking about the act of Jauhar, Mulla Ahmed calls it “an act of great devotion.” Abul Fazal’s estimation of around three hundred women burning is also wrong. The number must have been bigger than that.

History remembers the act of Jauhar by these women but it fails to highlight their courage on the battlefield too. Yes, not only the men but also the women fought and perished in the battlefields. One incident during the third siege of Chittorgarh by Akbar stands out particularly. In Tod’s Annals of Rajasthan, The Annals of Mewar, James Tod narrates the following incident.

When Shahidas fell at Gate of the Sun (Suraj Pol), the command devolved on Patta of Kailwa. He was only sixteen. His father had fallen in the last siege, and his mother had survived but to rear this the sole heir of her house. Like the Spartan mother of old, she commanded him to put on the saffron (Kesariya) robe and to die for Chittor; but, surpassing the Grecian dame, she illustrated her percept by example; and, lest thoughts for one dearer than herself might dim the lustre of Kailwa, she armed his young bride with a lance, and the defenders of Chittor saw the fair princess descend the rock and fall fighting by the side of her brave mother (Mother-in-law)

When their wives and daughters performed such deeds, the Rajputs became reckless of life. Patta was slain; and Jaimal, who had taken his place, was grievously wounded. Seeing there was no hope for salvation, he resolved to signalize the end of his career. The fatal Jauhar was commanded…

Kirthi Stambh at Chittorgarh

The young bride fought alongside her mother-in-law and perished on the battlefield. The mother not just motivated her son to don saffron robes (Saffron is invariably linked with sacrifice) but also went out to war herself. This one incident shows that there were at least a few incidents where the women died fighting a fierce battle. They were not cowards who opted for suicide. They were brave women who, when driven to extremities, opted to die an honorable death than live a life of humiliation. The reasons for the same will be discussed sometime later in this article.

Some even went as far as calling Rani Padmini a myth, a story that has been propped up over the years to glorify this cruel practice.

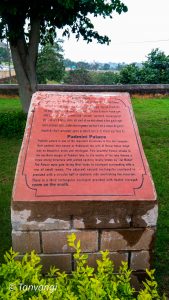

Be as it may, Rani Padmini palace is a well-marked site at the Chittorgarh Fort and her Jauhar finds a mention on the plaque place on the fort. Although tracing her history through primary sources is a murky business, these well-marked places exist on the fort. Anyways, her existence in history is not the point here.

Plaque outside Padmini Palace

The practice of Jauhar is an old and a well-documented one. Most cases of Jauhar have been documented in the northern states, although, there is at least one mention of Jauhar in the state of Karnataka.

Chittorgarh itself saw three Jauhars spanning a time of two centuries. The first one being in the 14th Century when Allaundin Khilji attacked Chittorgarh in 1303 and Rani Padmini, along with the rest of the women present on the fort committed Jauhar.

The next one was the Jauhar committed by Rani Karnavati in 1535 when Bahadur Shah of Gujrat breached the gates of Chittorgarh. 16th-century Chittorgargh witnessed one more Jahur in 1567 when Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar attacked the fort. Each of these times saw huge furnaces being lit and the women and the children on the fort burnt themselves alive along the old people and the men went out to commit Saka. The last one has been described in detail above.

Jauhar that happened in Karnataka happened sometime in the 14th-century when Muhammad Tughlaq marched southwards against the Kampila kingdom. It is believed that the Raya (the king is called Raya in these parts) had given refuge to Baha-ud-din Gushtasp, the rebel nephew of Muhammad Tughlaq. There is a conflict in this version of the story with two different people telling two different reasons for this march but one thing is sure that Muhammad Tughlaq had indeed attacked the Kampila kingdom.

The Raya faced Muhammad Tughlaq’s army from the fortified region of Anegundi. With the Sultan’s army at the gates, a huge fire was lit and in which his wives, the wives of his nobles and other important men immolated themselves. The men went to war after this and the Raya was slain.

It is from the ashes of Kampila Kingdom that the great Vijayanagar empire rose and prospered.

As mentioned earlier, this mass suicide followed by men setting off on a one-way suicide mission with the intent to perish while fighting was done only when the enemies were Islamic invaders and not when the invading king was a Hindu.

What was the reason for this? What prompted these brave women to give up their lives in such a terrible manner? And why only in the face of an Islamic invasion? The reason lies in the treatment meted out to the defeated side.

Mercy and dignity were expected for the defeated and his family and especially his women when the attacking army was commanded by a Hindu king. Whereas Islam allows taking in slaves. Some startling facts emerge when the pattern and statistics of Islamic slavery are studied and compared with American slavery. This study was conducted with respect to the African population.

Peter Hammond in his book Slavery, Terrorism and Islam: The Historical Roots and Contemporary Threat observes that two women for every man were enslaved by the Islamic slave traders. He estimates that around 28 Million Africans were enslaved by the Islamic Middle East out of which nearly 80% died before even reaching the slave markets. The death count of Islamic slave raids into Africa, over the last fourteen centuries, is estimated at 112 million. An important point to be noted in this is that out of these slaves there were two women to one man.

Islam, right from its inception has always been an expansionist religion. According to Islam, anyone not following the path of Allah is a Kaffir and a Kaffir can be deceived, plotted against, hated, enslaved, mocked, tortured and worse. A Kaffir woman, captured and enslaved is at the mercy of her master. The women were invariably added to the harems of these warlords and in case of invasions in India, these poor women were added to the harems of the ruling Sultan, to be used and abused in whichever way the Sultan deemed fit.

Polygamy is encouraged in Islam and although a man can have only four legal wives, he can have as many concubines and slave-girls as he wants. He was allowed to cohabit with them. There was a reason for slaughtering men and taking women and children as captives. Women were considered more malleable than men. Also, any children that they bore would automatically adopt the faith. Captured children were forcibly converted.

This system of polygamy and acceptable slavery was also followed by the Sultans who ruled over India. Any woman falling into their hands was invariably added to the Sultan’s harem as his concubine. To save themselves from enslavement, rape and forcible conversion, these brave Rajput women committed Jauhar.

An example of Aurangzeb’s treatment and behaviour towards unfortunate women who survived their attempt of committing Jauhar.

… Next September he (Aurangzeb) was sent to suppress the Bundela rebellion, at the head of three armies. The issue of that expedition again typified the character of the supreme commander: the survivors of Jauhar were dragged to the Mughal harem; two sons and one grandson of Jajhar were converted to Islam; another son and minister of the Raja, having refused to apostatise, were executed in cold blood.

This same incident has been described in a little more details by G B Mehendale,

Jujhar Singh of Orchha was a mansabdar of the Mughal Empire. Shah Jahan sent a large force against him because he had rebelled, upon which he fled into the territory of Chanda. When he realized that his pursuers were closing in upon him, he attempted to kill the womenfolk in traditional Rajput manner. However, just when some of the women had been dispatched, the Mughals fell upon him and captured the survivors. Parvati, elder consort of Jujhar’s father Bir Singh Dev, died from her wounds. Jujhar sun, Durban, and Durjansal, grandson from his elder son Bikramjit, were taken captive. Another son. Udaybhan, along with a younger brother and a trusted follower called Shyam Duda fled into Qutbshahi territory. Jujhar Singh himself and Bikramjit took cover in the forest where they were killed by the Gonds. The surviving womenfolk along with son Durgbhan and grandson Durjansal were brought before Shah Jahan who ordered their conversion to Islam. They were duly converted and given the names Islam Quli and Ali Quli respectively. while the womenfolk, also converted to Islam, “attained the fortune of serving in the heavenly harem” (or, in plain language, Shah Jahan turned them into his concubines). The Qutb Shah arrested Udaybhan, his younger brother and Shyam Duda, and sent them to Shah Jahan. The younger brother was ordered to be converted. Udaybhan and Shyam Duda, being older in age, were given the choice between conversion and death. They chose the latter and were duly executed.

Another incident from Shah Jahan’s rule.

Pratap, the chief of Ujjaniya near Buxarrebelled against Shah Jahan. Towards the end of November 1636, the emperor ordered the Subhedar of Bihar, Abdullah Kahn Bahadur Firoz Jang, to march against him. Pratap was ensconced in the Bhojpur fort, which the Subhedar invested. Soon, Pratap sued for peace, saying he was at Subhedar’s mercy and surrendered on 25th April 1637. Abdullah Khan imprisoned Pratap and his wife and put their followers to death. On learning of these developments, Shah Jahan sent an order for Pratap’s execution and for taking his wife into custody, whereupon Abdullah Khan converted the lady to Islam and married her off to his grandson.

Another instance from the times of Akbar as described by Abul Fazal in Akbarnama.

When the brilliancy of the Rani’s rule was extinguished, and when in the very height of her rule the hand of the destruction flung the dust of annihilation on the head of that noble lady, Asaf Khan after two months, and when his mind was rest about Miyana country proceeded to the conquest of Cauragarh fort. This fortress was replete with buried treasures and rare jewel, for the collection former Rajahs had exerted themselves for many ages. They thought these would (be) a means of safety but in the end they were a cause of destruction. The soldiers girded upon the loins of courage to capture this golden fort, and from the love of these treasures, they washed their hands of life and eagerly followed Asaf Khan. The Rani’s son, who had left the battlefield and was shut up in the fort came out to fight on the approach of the army of fortune, but the fort was taken after a short contest. The Rajah died bravely. He had appointed Bhoj Kaith and Miyan Bhikari Rumi to look after the Jauhar, for it is the custom of Indian Rajahs under such circumstances to collect wood, cotton, grass, ghee and such like into one place, and to bring women and burn them, willing or unwilling. This they call the Jauhar. These two faithful servants, who were the guardians of honour, executed this service. Whoever out of feebleness of soul was backward (to sacrifice herself) was, in accordance with their custom put to death by the Bhoj aforesaid. A wonderful thing was that four days after they had set fire to that circular pile, and all that harvest of roses had been reduced to ashes, those who opened the door found two women alive. A large piece of timber had screened them and protected them from the fire. One of them was Kamalvati the Rani’s sister, and the other was the daughter of Rajah Puragadaha whom they hah brought for the Rajah but who had not yet been united to him. These two women, who had emerged from that storm of fire, obtained honour by being sent to kiss the threshold of the Shahanshah.

It was not a one-off instance when this happened. This was a pretty common practice. There are many recorded instances wherein young princes were forcibly converted, effectively preventing them from claiming the throne at a later date.

Many factors contributed to this practice. It had a lot to do with the contemporary social environment. If living meant living a life of humiliation and bondage, death was preferred by these women. This practice looks cruel to modern eyes but those were barbaric times and surrounded by hostile Islamic rulers who practised and promoted flesh trade and slavery, death by burning was a more dignified than the life of a slave.

Jauhar was medieval practice born out compelling contemporary social conditions. This practice doesn’t find any support or even a mention in any of our scriptures. Our scriptures, in fact, stress against self-harm in any form. I reiterate that Jauhar was opted for only as a last resort and only in face of Islamic invasions where the chances of getting enslaved and losing dignity were high. Calling these brave women cowards or saying that they opted for an easy way out is a great disservice to them and their memory.

Refrences

A Forgotten Empire (Vijaynagar) by Robert Stewell Pg 16-18

The Hadidth: The Sunna of Mohammed by Bill Warner

Mohammed and the Rise of Islam by David Samuel Margoliouth Pg 97

Akbar Nama of Abul Fazal translated by William Jones (Multiuple pages)

Mntakhab ut-Tawarikh by Abd al-Qadir Badayuni Pg 106-107

Tods Annals of Rajasthan: The Annals of Mewar Pg 70

Mughal Empire in India: A Syatematic Study Including Source Material by S.R Sharma P 457,458

Shivaji His Life and Times by G B Mehendale P 54

History of India As Told By It’s Own Historians

All information entered is personal to the author. Any modification or changes must be addressed to the author.