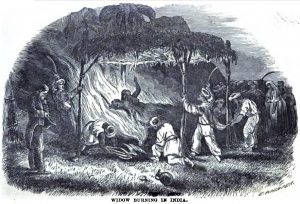

Widow Buring in India August 1852

Over the last many years, it has become a trend to vilify and condemn Sanatan Dharma or Hinduism as westerners call it. Anyone showing even an iota of respect or pride in Dharma is shamed and mocked for being a supporter of a barbaric and cruel faith. Many practices are used to vilify us. Prominent among them are the Varna vyawastha, Sati, child marriage, untouchability, lack of education for women and not allowing the widows to remarry.

What many people fail to realise is that historicity of a certain event doesn’t grant it scriptural sanction. There is no founder of Santan Dharma. It has existed since times immemorial. Although the basis of Dharma, the four Vedas have not changed over the years, it has evolved with time. And with evolution comes changes.

Some practice evolved with time. Some went out of practice and new ones replaced them. Many were forgotten as time went by and some continued to exist with a changed form. Dharma has remained constant over the years but the rituals, traditions and practices changed as per the times.

With the advent of the Islamic invasions, it became unsafe for women to move around freely. They were increasingly confined to their homes but to say that Sanatan Dharma dictates that women stay confined in their homes is unfair. There have been numerous Rishikas who were well known for their knowledge. It was once a free society but somewhere along the line, it became narrow and closed. There are historical reasons for the same.

Dharma has always placed women in high regard with people belonging to the Shaakt sect placing the Tridevi i.e. Maha Saraswati, Maha Lakshmi and Maha Kali even above the Trimurti, Bramha Vishnu Mahesh. But despite this, some practices that developed over the years due to circumstances and which are by no means sanctioned in the Vedas are used to malign Sanatan Dharma.

Many examples in history are stated to justify the claims of Sanatan Dharma being regressive and barbaric. Feminists come forward to condemn these practices in strong words and western intellectuals hasten to take credit for abolishing these practices from our society. Invariably, a woman is a victim in this narrative and is supposed to be grateful to Britishers for saving her from the barbaric and inhuman faith. We are repeatedly told, via education and mainstream media that we were savages who were first civilized by Mughals and then by the Britishers.

One of the practices used to shame us is the practice of Sati.

Sati is a practice/ritual where a widow self immolates herself on the chita or pyre of her husband post his death. It was a choice that was given to her. Nowhere is it mentioned in our scriptures that Sati was compulsory. There are some examples of Sati in Mahabharat and none in Ramayan, which pre-dates it by many centuries.

(There is a mention of Sati in Uttara Kand but that part is considered to be later addition.) 1

There are many examples of a woman having survived her husband by years. Devi Kunti survived her husband Maharaj Pandu by many years. Even Maharani Satyavati survived her husband Maharaj Shantanu by many years and so did Uttara. Our scriptures mention this practice as a choice at best.

Historically, this practice was prevalent among women belonging to the warrior class only.2 It spread to the other classes much later. Wives of Brahmins were actively discouraged from participating in this ritual.3

The general perception, thanks to the British government that ruled us for nearly a century and a half is that Sati was rampant in all of India and that thousands of unhappy widows were burnt each year. Some willingly and many forcefully. But even a cursory study of statistics of Sati brings out some startling facts.

Sati was not as rampant as Britishers led us to believe. The numbers were grossly hyped up by the British Government and the missionaries who had collected the data.

In the year 1813, William Carrey says, and here I quote, “Besides these, I calculate 10,000 women annually burn…” 4

An important point to bee noted here is that William Carrey’s work was limited to the Bengal area.

In the year 1803 Carey conducted a survey wherein he recorded the total number of Satis occurring within 30 miles radius from Culcutta. The number stood at four hundred and thirty-eight. The next year he placed ten men at regular intervals in the same radius and they reported to him for six months. The number of Satis in those six months stood at between two hundred to three hundred .5

He applied this data collected from the small area of 30 miles around Culcutta to the entire country and concluded that around 10,000 widows burn annually.

But the data published by Edward Thompson just a few years later in terms of the number of Satis is vastly different. Data collected over thirteen years show that barely 5099 cases were registered in Calcutta division, still, a high number as compared to other divisions. Bengal, however, then, included Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa and Assam. 6

As per Carey’s calculations, around 10,000 widows burnt each year in India but the data collected by Edward Thompson just a few years later showed that barely 9000 cases occurred in thirteen years.7

Although this statistic is limited to certain divisions, Dr Altekar gives a general idea of the number of Satis occurring annually in Bombay and Madras presidency according to the Government records was well below fifty and in the Poona domain, which was under the Peshwa, the annual average was about twelve. Central India had only an average of three or four cases per year. 8

Thus, it is clear from the above statistics that the customs of Sati was most prevalent in the Bengal area and was not so popular in the rest of the country. There are many instances of people having dissuaded their relatives from becoming a Sati.

Few examples are:

- When the father of Gangabai Sathe, the wife of Narayanrao Peshwe died, her mother wanted to become Sati. She was discouraged from doing the same.

- Ahilyabai Holkar survived her husband and also did her best to dissuade her daughter from mounting the pyre of her husband. Although she was unsuccessful in doing so and her daughter became Sati, this and the above incident is a testimony of the fact that many times women were actively discouraged from becoming Sati.

This is not to say that no incident was forced. No widow was burnt against her wishes. They may have been some incidents that were forced but most were voluntary. Social pressure and faulty understanding of scriptures coupled with greed for the deceased man’s wealth may have led to these unhappy incidents. But to say that all Hindus were monsters who burnt their women is unfair.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the practice of Sati was officially discouraged/banned by the Peshwa of Poona and the Maratha government of Sawantwadi. 9

Prof Meenakshi Jain in her book Sati: Evangelicals, Baptist Missionaries, and the Changing Colonial Discourse, says that the descriptions of Sati can be divided into two parts. Pre and Post Baptist phase. In the Pre-Baptist phase, the description was provided by various travellers who were mere observers of the local culture and practices. The tone was that of awe and wonder at the courage of the woman unwilling to live without her husband.

Some examples of various travellers describing instances of Sati that they heard of or witnessed.

- Tavernier, 17th-century traveller gives details of an incident that he witnessed in Patna. He was sitting in the Governor’s house when a beautiful woman of not more than twenty-two years entered the Governor’s house with a request that he allow her to burn along with her deceased husband. The Governor tried to convince her otherwise but to no avail. Thinking that the Governor felt that she would not be able to bear the agony of being burnt by fire, she asked him to get a torch for her. The Governor was horrified by her request but some of the young nobles present persuaded him to allow someone to bring a lighted torch to test the woman’s resolve. They were very sure that she would not be able to pass the test. A well-lighted torch was allowed to be brought and as soon as she saw the torch, she ran towards it and firmly held her hand in the flame without betraying any signs of discomfort or agony. She continued to advance her hand until the flame consumed her hand up till her elbow. 10

- Ibn Batuta, a 14th-century traveller describes one such scene in detail. This incident happened in Amjari (Amjhera near Dhar). He saw three women whose husbands had been killed in a battle and they had agreed to burn themselves with their husbands. He describes the process in detail. In short, the woman becoming Sati was dressed in rich and perfumed clothes and was taken in a procession which included her relatives and Brahmins. Drums were beaten and trumpets were blown. The relatives gave her messages that they wanted her to carry to her deceased husband which she accepted. She carried a coconut in her right hand and a mirror in her left. He then goes on to describe a cremation ground and in his words, ‘The place looked like a spot in hell.’ It had a basin of water (presumably a lake) which had four pavilions with a stone idol in each of them (again, presumably temples with Murtis). These temples had steps that led to the lake and the widow descended the steps to this lake and plunged into it. She got rid of her clothes and was given a coarse unstitched garment to cover her waist, shoulders and head. Her ornaments and clothes were distributed as alms. The pyre was lit and sesame oil was poured into it which stoked the fire. The fire was screened from her view by a blanket. He describes that one of the widows pulled the blanket screening the fire aside and smiled and asked “Do you frighten with the fire? I know that it is a fire, so let me alone.” She then saluted the fire and jumped into the fire. Drums were beaten and the trumpets were blown and the bugles were sounded and heavy pieces of wood were put on her to prevent movement. Ibn Batuta says that he nearly fainted at that sight and then withdrew from the spot.11

- Francois Bernier was a French physician and traveller in Mughal India, precisely during Shah Jahan’s reign, he was briefly the personal physician to the Mughal prince Dara Shikoh. He was in Surat when he witnessed a Sati. He says, and here I quote, “ She was of the middle age, and by no means uncomely. I do not expect, with my limited powers of expression, to convey a full idea of the brutish boldness, or ferocious gaiety, depicted on this woman’s countenance; of her undaunted step; of the freedom from all perturbation with which she conversed, and permitted herself to be washed; of the look of confidence, or rather of insensibility which she cast upon us; of her easy air, free from dejection; of her lofty carriage, void of embarrassment, when she was examining her little cabin (the pyre), composed of dry and thick millet straw, with an intermixture of small wood; when she entered into that cabin, sat down upon the funeral pile, placed her deceased husband’s head in her lap, took up a torch and with her own hand lighted the fire within…” 12

- Pietro Della Valle was an Italian composer and author who travelled in India in the 17th-Century. He says, and here again I quote, “If I can know when it will be I will not fail to go to see her and by my presence honour her funeral with the compassionate affection which so great conjugal fidelity and love seem to me to deserve.”13

These are just some of the more popularly known examples. All of these travellers, spanning over different centuries, describe the resolution and the courage of the woman who is becoming a Sati. They are in awe of her courage and devotion towards her husband. The tone of descriptions of Sati changed only in the Post Baptist phase.

As mentioned earlier, William Carey was probably amongst the first people to formally collect statistics regarding Sati. His estimate of nearly 10,000 widows burning annually is at best faulty and at worst a malicious attempt to paint Hinduism as barbaric. Statistics collected by his contemporaries tell us otherwise.

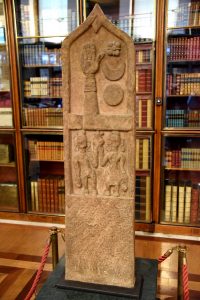

Sati Stone memorials to Indian widows found all over India, 18th century CE currently housed in the British Museum

So, who was William Carey and why is his name so important when we speak of Sati?

William Carey was a British Christian missionary who arrived in India sometime in the last decade of the 18th-century. He witnessed his first Sati in the year 1799 in the village of Noya Serai.14

In his letter addressed to someone named Ryland, he describes how he attempted to reason with the people who had gathered to witness the woman becoming a Sati saying that it was nothing but murder. He describes how he had tried to convince the woman that she need not become a Sati but to no avail. same as 14

The contempt which he held for idolatry and Hindu practice is clear from his letter written on October 6th 1800.

… This part of the country is very populous indeed, and wholly given to idolatry. It is not possible to describe the stupidity of the worship or the strength of their attachment to the customs and practices of their forefathers. We preach to them, converse and dispute ith them; visit them at their houses, and are now printing the word of God in their language. The Gospel of Matthew has been dispersed, and also several other pieces calculated to strike their Hearts and engage them to think of their immortal Soul. At present, however, very small fruit appears, tho perhaps we sometimes overlook what would be esteemed very great effects, was it not that their appearing so gradually they don’t strike us much…15

This letter from 1800 shows that his attempts at converting the indigenous population were not much of a success and that held the local customs of Idolatry to extreme contempt. In the same letter, he mentions that, although he faced resistance, the resistance was not very violent and that he did not face any personal danger.

His missionary work is very briefly described in a paper titled ‘Hinduism in India and William Carey’s Approach to People of Other Faiths’.

Here again, I quote from the paper, ‘Shortly after his arrival in India, in the year 1802, he began an investigation on the commission of the Governor into religious killings among Hindu people in India, and very soon he got the result.’

This is corroborated in a letter addressed to Fuller in January 1802.

Several religious murders were lately detected at Langur island, which is just at the mouth of the holy Ganges. In consequence of which I as Teacher of the Bengali language received an order from the vice President through the medium of Mr Buchanan to make every enquiry which I can into the number, nature, and reasons of those Murders, and to make as full a report as I can of the whole to the government.16

In the same paper, ‘Hinduism in India and William Carey’s Approach to People of Other Faiths’, and here I once again quote;

“At last because of Carey’s revolutionary attempt, William Bentinck passed a regulation on December 4th 1829, declaring Sati as an illegal and criminal practice.” So we can safely say that he had a major hand in getting the data that prompted the law.

He had a major role to play in getting the practice of Sati officially abolished. Even before the practice was abolished completely, he worked to influence young minds that he taught in Fort William College to oppose this practice. Many widows were thus saved from burning.

As mentioned previously, the tone in which Sati as a ritual was described changed in the Post Baptist period. Many missionaries arrived in India and began to create awareness about evils withing the Hindu society. Along with that, they also began their missionary activities. They faced resistance in the initial stages as mentioned by Willam Carey in his letter. They began studying Hindu scriptures and began translating the Bible in local languages. William Carey is credited for having translated the Bible in Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, and Sanskrit. He edited, with Marshman, a grammar in Bhotia and prepared six other grammars in different languages. In addition to dictionaries in Bengali, Sanskrit, and Marathi, Carey and Marshman prepared a translation of three volumes of the Hindu epic poem Ramayana.17

From the above-mentioned statistics, it is clear that Carey’s calculations were wrong and the practice of Sati was not so widely practised in India. Bengal had a relatively high number but that was just one area. As Dr Altekar says, one in a thousand woman became Sati. That is how rare this practice was.

So is it possible that William Carey deliberately hyped up the numbers?

Yes, it is very much possible that he may have hyped up the numbers. He was, after all a Jesuit missionary whose sole aim was to spread the word of Jesus. The widows he ‘saved’ were converted to Christianity and then he arranged marriages for them. 18 Hyping these number benefitted them. They got to convert more people under the guise of ‘protecting them from evil and barbaric Hinduism.’

That which he didn’t understand or comprehend, he labelled it as Satanic.

“On this Day the Hindus keep a day of Gladness and feasting, being the first Day of their year – they, nor their Cattle do any kind of Work, but spend the time in Singing and Joy – Indeed these Horrid and Idolators transactions have made such an impression on my mind that I think cannot be easily eradicated – Who would grudge to spend his life and his all, to deliver an (otherwise) Amiable People, from the misery and darkness of their present wretched state, and how should we prize that Gospel which has delivered us from hell, and our Country from such dreadful marks of Satan’s Cruel Dominion as these.19

Even celebrations of the new year seemed Satanic to his mind. Such was the deep hatred and contempt for Idolatry in his mind.

While the government had it’s own agenda to fulfil. They got a chance to justify the forceful colonization of the land. The British Government came out as saviours of the poor widows instead of being seen for what they really were, gross violators of the indigenous population’s freedom. The fact that Marathas and Peshwas had banned Sati a long time before the British government even thought about it is conveniently erased from the collective minds of the society and the British become the sole saviours who modernized and civilized us.

An entire generation got fooled into believing that Britishers were the saviours which were far from the truth.

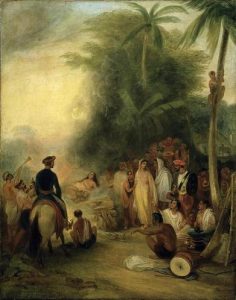

Suttee by James Atkinson

References

- Position of Women in Hindu Civilization by Dr A S Altekar, Pg-142

- Position of Women in Hindu Civilization by Dr A S Altekar, Pg-142, 143, 147

- Position of Women in Hindu Civilization by Dr A S Altekar, Pg-151

- An Apology for Promoting Christianity in India by Claudius Buchanan, Pg-30

- A View of the History, Literature and Religion of the Hindus: Including a Minute Description of their Manners and Customs and Translations from their Principal Works Volume II By William Ward, Pg-312

Sutte: A Historical and Philosophical Enquiry into Hindu Rite of Widow Burning by Edward Thompson, Pg- 60,61

An Apology for Promoting Christianity in India by Claudius Buchanan, Pg 8

6. Taken from Position of Women in Hindu Civilization by Dr A S Altekar, Pg-164

Original reference from History of British India IX by Mill and Wilson, Pg 271

7. Position of Women in Hindu Civilization by Dr A S Altekar, Pg 163

8. Position of Women in Hindu Civilization by Dr A S Altekar, Pg 163

9. Position of Women in Hindu Civilization by Dr A S Altekar, Pg 165

Sutte: A Historical and Philosophical Enquiry into Hindu Rite of Widow Burning by Edward Thompson, Pg- 58, 59

10. Travels in India by Jean Baptiste Tavernier, Pg-220 to 222

11. Travels in Asia and Africa by Ibn Battuta, Pg- 192, 193

12. Travels in the Mogul Empire Volume II by Francois Bernier, Pg-16

13. Travels of Pietro Della Valle in India Volume II by Pietro Della Valle, Pg-267

14. The Journal and Selected Letters of William Carey, Pg-79, 80

15. The Journal and Selected Letters of William Carey, Pg- 80, 81

16. The Journal and Selected Letters of William Carey, Pg 81

18. Willam Carey: A Tribute by a Indian Woman, Pg-8

19. The Journal and Selected Letters of William Carey, Pg-24

20. Image source Wikipedia

All information entered is personal to the author. Any modification or changes must be addressed to the author.